With special thanks to all of the sponsors who have helped make this project happen so far: Zermatt Tourism,Jungfraujoch Top of Europe and The Altitude Centre

When we first got into adventure, we started out exploring our local hills.These didn’t really pose much of a problem in terms of our abilities but, as our appetite grew, so did the size of the mountains and landscapes that we found ourselves longing to be a part of.Both of us grew up in and have spent most of our lives inhabiting low-lying cities andwe didn’t really have much experience in environments over 1,300m above sea level.On our first trip to Austria a couple of years ago, we headed to Grossglockner.At 3,798m this is Austria’s tallest mountain.We didn’t summit it, but our visit did take us to over 2,500m. This certainly made us realize that we felt much more out of breath than we did back home in London.Over subsequent years our travels took us to more and more high-altitude locations, but this experience nearly always comprised day hikes or trips to mountain tops via cable car.

Some time ago and inspired by a film that’s almost one hundred years old, we began research on a new project. This would be the biggest project we have ever worked on and would take us to some of the highest and most extreme environments in the world. Extreme environments later, but for now, let’s stick with altitude.

We started planning this project in much the same way we approach any project; think of the big idea and work backward; creating a series of achievable, stepping-stone goals to make it happen. The one thing that we both agreed on straight away was that we needed much more experience in high altitude environments before we could even begin to start thinking about creating the bigger, end game project. The environments we’d need to have access to in order to make the project work, would, if not treated properly and with an adequate skill level, be potentially deadly. We also had concerns about how we’d feel in these environments. As photographers, we wanted to get a handle on how we’d be able to work at altitude rather than just survive. We needed to learn the workarounds we’d need to build in as habitual patterns before we attempted our ‘big project’.

Being at altitude is tough on the body for sure, but it shouldn’t be something that scares you away from the adventures you want. If you’re finding yourself called to experience even more of what the world has to offer, there will most likely come a point when altitude becomes something that you need to develop a relationship with.

Just to be clear, we’re not in any way trying to suggest that if you go on many trips at altitude, you’ll be able to handle another trip without a care in the world – that isn’t how acclimatization works. What we are saying is that you can massively improve your chances of enjoying and being able to be competent at altitude if you have experience at altitude, know how your body handles it, work around problems and know when enough is enough. So, when it comes time to set off on that trek you’ve always wanted to do, you’ll have all of the skills you need and know how to look after yourself based on your previous experience at altitude. It’ll massively remove a lot of the anxiety of all of those unknowns, meaning you’ll go into it enjoying it.

Plus, you can have a lot of fun on the journey leading up to it!

We decided to plan our first working at altitude trip to The Alps this summer around a number of environments that were higher than we’d ever really been for prolonged periods. Usually, and without conscious effort, in the past, we’d go higher in the day and sleep lower at night. This would still be our tactic here, but we’d increase the ‘starting point altitude’ of both. We had three parts to this trip; The Bernese Alps, Switzerland would see us sleep at 1,500m, Gran Paradiso, Italy, 2,000m, and Zermatt, Switzerland 1,600m. In the daytimes, our itinerary would see us venturing up to 3,883m at our highest point. We had a number of photographic commissions happening in each place, so this would be a fantastic opportunity to really start putting into practice our need to learn how we could work at altitude.

Training for the trip was much the same as any other trip, with a notable exception.Prior to our departure we teamed up withThe Altitude Centre in The City of London to evaluate how Hypoxic Training could benefit us.If you are not familiar with the term, Hypoxic Training means that you are deliberately reducing the amount of oxygen you have access to during exercise.Broadly speaking, the idea is that oxygen is a fuel your body needs during exercise and by deliberately reducing this, your body gets used to performing with fewer resources – basically, you become more ‘efficient’.This has two benefits: first, it gets you used to exercising at higher altitudes and second it means that when you exercise at sea level, you can work harder, walk further and faster and so on.Many people will know that elite athletes often train at high altitude (the US Olympic Committee has a training facility in Colorado Springs at 1,800m for instance) and this is precisely so that they gain the benefit of the hypoxic effect.The cardio equipment at The Altitude Centre – treadmills and Watt Bikes – are housed in a special room where the air pressure is dropped to mimic conditions at 2,600m.They also have a high altitude ‘breathing pod’ – essentially an oxygen mask that mimics altitudes up to 6,000m.

As we were training for mountains, our regime centered on the treadmill.A typical workout lasted one hour and was broken into five-minute blocks.Keeping a consistent walking pace, we would alternate between a steep twenty-degree gradient and a shallower, but still uphill gradient – usually around eight to ten degrees – for each block.It may not sound very intense, but with the thinner air we certainly felt the workout!Typically, after an hour, the treadmill would report that we had climbed over 600m, so the exercise was far from trivial!From a sports science point of view, plenty has been written about hypoxic training and there are plenty of studies that both praise its benefits and question its value.

Did we experience any benefit from hypoxic training?Well, there was certainly a benefit, but we think it would be difficult to directly prove how much of it came from the fact that we were working out in hypoxic conditions rather than simply working out.None the less, whilst the effects of altitude still hit us on some days on our trip, from a purely fitness point of view, this wasn’t too severe, so whilst this cannot be a scientific conclusion, we would say that the time we spent at the Altitude Centre was definitely beneficial – though in the short time we had before our trip, the benefit was certainly subtle.If you are interested in climbing further and higher as we are or, if you are planning a trip that will push you to your absolute limits, then hypoxic training is well worth investigating.The fact is that it won’t be an option for many of our readers as gyms with these facilities are few and far between, but if the option is there, then it is worth considering seriously.As we have learned from the world of professional cycling, ‘marginal gains’ can make all the difference!

When we set off for our first leg of the trip, we arrived really late in Sedrun, at around 1,500m above sea level in the Bernese Alps of Switzerland. We were really tired after a long 14-hour drive from London but woke up the next day to beautiful sunshine that could not be ignored. Looking at the weather reports for the following couple of days, we were very concerned by the constant heavy rain and thunderstorms that looked likely to grace us with their presence. It wasn’t ideal to head out that day after such a long, tiring drive the previous day, but we took the opportunity to hike in an area we knew well already from a previous trip. We wouldn’t go and do anything particularly intense, but we’d head up to over 2,000m, do some shorter hikes and start to photograph. We’re not sure if it was the training at The Altitude Centre that helped or the fact that we already had experience at this altitude, but we felt fine. We soon started to feel tired though and working became exactly that; work. The tiredness was most likely down to the lack of sleep and long hours of concentrating on an intensely long drive the previous day. In the past, we probably wouldn’t really have made that distinction.

The following day we decided to rest. It wasn’t such a problem anyway, as we had really bad rain and thunderstorms with little to no visibility, so hiking would have been a pretty dumb move. We were hoping to wake up the following day to a much more hike-able day, however the storms hadn’t passed, and we were left with conditions that just wouldn’t have made hiking possible. Even though we weren’t at a crazy high altitude at our Airbnb, we still saw this as a really great way to acclimatize to the thinner air.

The following day, we were due to work on a job withJungfraujoch Top of Europe, which would take us to the highest altitude we’d been to at 3,466m above sea level (and you can see more about this by clickinghere). We couldn’t wait to see how we felt and worked at this altitude. As we got off the train at the visitor center, we saw people immediately start to feel out of breath and start freaking out. We were very well aware that, for a lot of people on the train, this was probably their first glimpse of a high-altitude landscape and unless you’ve purposefully researched it, may not be aware of how altitude can affect your breathing. It isn’t surprising to think that you might feel concerned if suddenly you’re gasping for breath walking up a flight of stairs that normally you’d have no problem with!

Our main aim here was to create an article about accessible high-altitude landscapes, but we also used this as an opportunity to see how we worked at this altitude. Matt found himself not quite as responsive as he would be at sea level and felt in some ways like he couldn’t quite be bothered to put in the same amount of effort that he normally would. However, he acknowledged that and realized that it was probably his body just being a little tired, especially from the starved oxygen in the air. Fay started to find that she needed to tell herself what she was going to do next; almost like ordering myself to do something. This seemed to work really well, and we soon clicked into the enjoyment of where we were. We generally felt like we did absolutely fine here, but also wondered how much being at altitude for a few hours really helped.

In the past, we’ve headed up to 3,000m on cable cars and found slight headaches coming on as the day goes by. We’d read that it can be useful to take ibuprofen leading up to being at altitude. We both took Ibuprofen regularly the day before and on the morning of this particular part of the trip and drank a lot of water. Headache free, we can say we think that it really helped. We started to realize that this was all about making new habitual patterns so that when we were at altitude, we could fall back on a set of ‘brain commands’ for when we were not as responsive as we would be at sea level. It was about trying to make ourselves as smart and sharp as possible to over compensate for the brain fog you get higher up. We took Ibuprofen for much of the trip, especially before the days we were going to head up to above 3,000m.

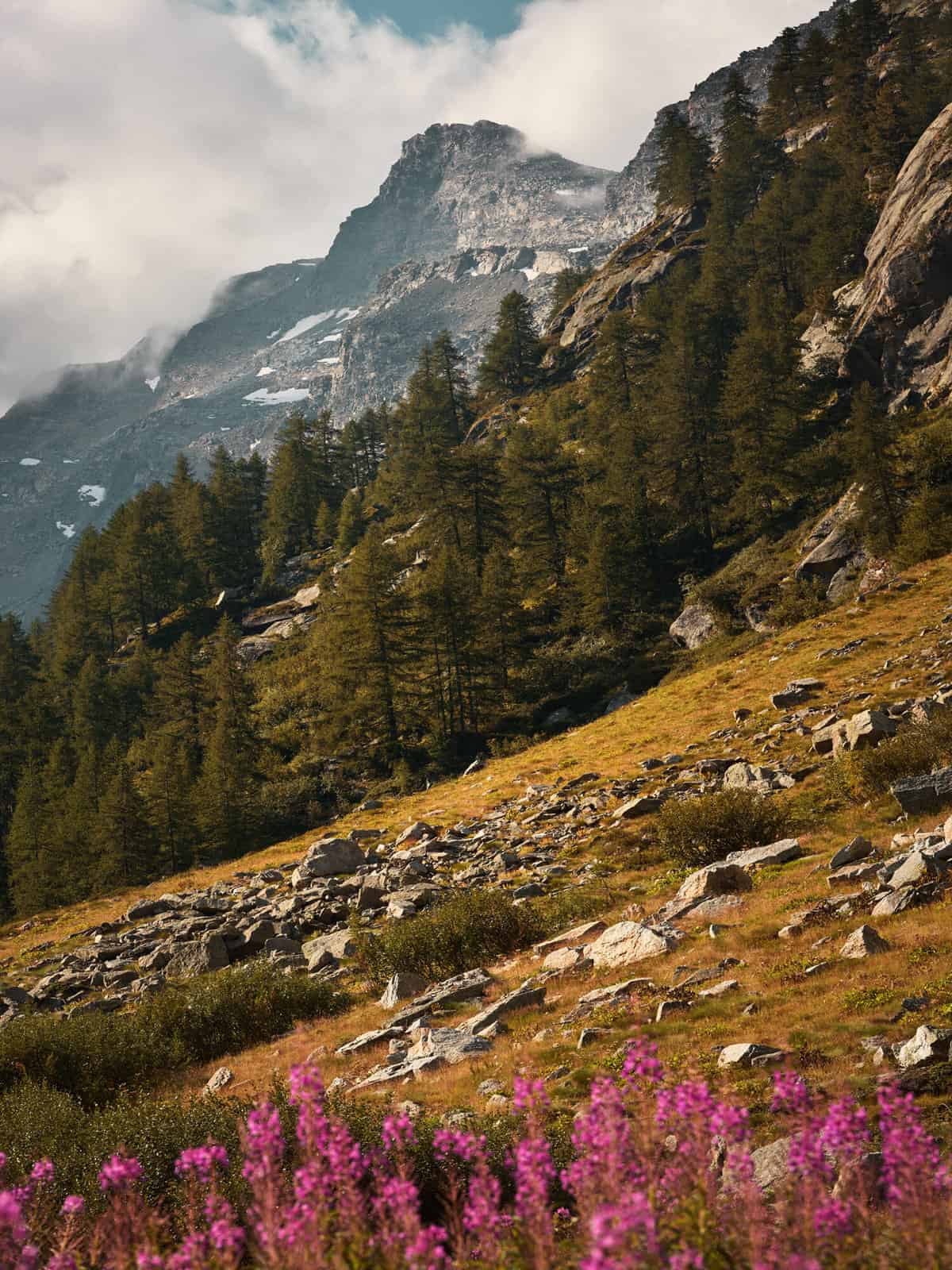

Our next destination was Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy, where we’d be camping in one of the many campsites available in the park, which you can read more abouthere. The next four days would put us at 2,000m above sea level with all of the hikes we had planned starting from the front door of our tent. We were really excited about this part of the trip, and in retrospect it was actually the most challenging part. Gran Paradiso is a fairly sizeable National Park, but unlike a lot of the Alps, the only way into a lot of it is to hike. This was certainly not a place with cable cars and mountain passes like many of the places we’d visited previously. It was obvious, here, you needed to work for your views.

We arrived later than we’d planned (traffic seemed to be a major factor with all of our driving distances on this trip) and were tired. Once we had our pitch, we went to set up and we’ve got to say, trying to inflate an air mattress at altitude posed a new problem we’d not really thought of! Fay set about making dinner and realized she was feeling a bit disorientated. She couldn’t work out if it was to do with the altitude or the tiredness from the setting up of everything, but she was starting to see that there appeared a connection between tiredness and altitude. When she set out to find the ingredients we needed for dinner, everything was all mixed around in the bags from the journey and it took her a really long time to find everything she needed. She started to feel really emotional and got really hard on herself because she felt a bit like a failure – she couldn’t even find the ingredients she needed for a meal. She quickly realized this wasn’t going to help her and realized she just needed to be kinder to herself. She quickly realized that her responses were slower at altitude. The views from our campsite more than made up for it though, and we felt genuinely moved by the big nature that was all around us, waiting to be explored.

Heading to bed, we both found ourselves waking up many times in the night, often feeling like we were gasping or coughing; this is meant to be quite common at altitude. The following day, we woke up early. It looked like there would be heavy rain in the afternoon and we’d made the decision to set off early on our first hike. We felt the air right away, and we found this really interesting. This was by far not the highest we’d ever been, but it was certainly the highest we’d ever slept. As we started to move, we kept the pace slower than we usually would on a lower altitude hike and this seemed to work well. The path for a while was gravel, which was easy going, but we both felt the air harder to breath almost immediately. As we began climbing up hill on the steep rocky steps, we felt clumsy; feet going one way and walking poles in the other. It was fine, but we both felt a need to keep an eye on each other as some of the clumsy foot moves could have resulted in twisted ankles. We realized at this point that we probably wouldn’t always feel like this at this altitude as we became more used to it, but for the time being, we needed to make sure we were really giving ourselves more care and attention than usual.

After a few km, we stopped for a break. We decided that we’d turn around and head back to the campsite, take a rest of a while and perhaps head out for another hike in the afternoon. Headaches and clumsiness started to come on as we got back to camp, and we set out our chairs in the sunshine and drank coffee. We felt so tired that we didn’t even think to reapply sun cream and came away from that morning with sunburn. We ate lunch which seemed to take about forty hours to make and remarked on how tired we felt. We involuntarily seemed to fall asleep for what felt like the whole of the afternoon; completely oblivious to the pouring rain that was hammering down on our tent. The rain stopped and we woke up and decided to go for another walk, this time, we’d just see how far we could get. We realized that our afternoon sleep and ibuprofen/water combo had helped and as we took it slowly, managed to go a lot further than we had earlier. The following day rolled in and we decided to take it easy for a few hours in the morning. The thing that we were finding here was that we had quite little motivation to do anything. We didn’t want to hike, shoot or really do anything. A running theme for us in this whole section was feeling a little like a failure and that we shouldn’t be feeling like this. ‘There are many people who spend their time at much higher altitudes than this, and they always seem fine’, we kept saying to ourselves. But this wasn’t helpful, and we spent a lot of time in inner turmoil trying to talk ourselves out of this. That afternoon, we both got really upset stomachs, headaches and just felt rotten. We took it easy that day much to our hatred apart from a relatively short hike.

We had plans at Gran Paradiso to spend so much time hiking, and on relatively challenging routes. What we were given, though, was beautiful scenery, shorter hikes and the perfect conditions to acclimatize for the third and final section of our trip in Zermatt, Switzerland. You have to take things as and where they are and move with that. Sticking to a rigid plan is literally going to strip you of your joy.

The final day, we set out on a hike and couldn’t have felt much more different from the previous days. We set out a little later, so that we’d had more sleep. We’d been taking ibuprofen quite regularly which had helped with our headaches and we’d done many smaller hikes to higher elevations and slept lower, so there was a good chance we were fairly well acclimatized by this point. We won’t go as far as to say that we breezed through the hike but going uphill didn’t really feel that bad. We felt ourselves wanting to shoot a lot more, and actually enjoying the scenery rather than just trying to power through it. Sure, this section of the trip didn’t go exactly as we’d planned, but by the end, we’d had a great lesson in being at altitude and how best to look after ourselves. We observed that in future we’d need to allow a couple of days to acclimatize in order to be able to make the most of things.

By the end of our Gran Paradiso section, we felt a lot sharper and much more ‘with it’ than we had before.

Zermatt would see us at higher altitudes than we ever had before but based on how we felt on our trip so far, were very confident about this. We were going to be creating some content for Zermatt tourism, and we saw this as a great opportunity to further work on how we were dealing with being at altitude and the work arounds to this that we were learning. Our first hike saw us begin at 2,500m, and we had absolutely no problem with it at all. We think it could have been that we’d settled into a pace and rhythm whilst hiking that seemed to work for us over the last few days. We were amazed by the scenery and our constant views of the Matterhorn and couldn’t get enough. The apathetic feeling of not wanting to photograph that we’d felt before certainly wasn’t a problem anymore! By the end of the hike, we’d noticed that the uphill sections had left us feeling quite heavily out of breath, but we handled it really well. We made sure we forced ourselves to eat as we found we didn’t think of food at all (appetite is something well known to decrease at altitude) and found it best to take snacks you’ll really enjoy (so we swapped trail bars for dark chocolate with nuts in). We felt pretty happy with ourselves and how we’d acclimated to this.

The following day, we headed up to the Matterhorn Glacier Paradise at 3,883m as part of our article for Zermatt tourism which you can read here. Sadly, we didn’t really get to comment too much on how the air felt up that high, as we didn’t spend too long up there. We had thick cloud roll in on our way up that completely blocked our views. Whilst we did have some truly incredible views on the cable cars up and down, we don’t really feel like we got the true experience there we were hoping for. However, one thing we’ve absolutely realized is that being at altitude for a couple of hours is not the same as being at altitude for a number of days. We’d always recommend that in order to acclimate properly, have the best chance of completing your hike and really enjoy your trip, to sleep at altitude and go higher and higher during the day, returning lower at night.

The rest of this trip saw us hiking at around 3,000m. We were very much aware of the altitude, but it didn’t affect us too badly and we really did feel like we were really well acclimated to that altitude. We’d worked really hard to put some of our new habits into practice; the slower walking pace, checking in on each other, realizing we would be more out of breath and being very mindful of our footing. With regards to photography, once we realized we had to pay more attention, such as checking photo exposure and such, we felt like we were doing well.

We came away from this experience feeling like we had a much better understanding of how we worked at altitude and how to compensate for it – we also felt quite a bit fitter and by the end of the trip on our couple of days break in Paris, we walked close to 30km in one day and didn’t even notice it.

What we’ve learnt so far as we prepare for our bigger project and start to get an idea of how we cope at altitude, is that it is nothing to be scared of. Of course, being aware of the serious signs of altitude sickness is incredibly important. It became clear to us that one of the biggest ways to see how you cope with altitude is to get used to how your body handles it in different ways. If you’re heading out on a hike at high altitude and you’ve never done anything like that before, you’re potentially going to derail your chances if you’re feeling really anxious about it and worrying every time you experience a new sensation in your body.

We found this experience to be invaluable in our development, and without it, probably wouldn’t feel as confident about the high-altitude trip we’re about to embark on in California. As we said, these goals don’t need to be big and unattainable, they can be achievable and manageable – and you can have a whole lot of fun seeing some amazing places along the way!