‘The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.’

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, Robert Frost

It’s a well-known poem. I think I first encountered it at Primary School, aged perhaps ten or eleven. I can’t be quite sure. Re-reading it now, close to thirty years later, the poem seems overly twee, sentimental, saccharine almost. There is no deeper substance or meaning. But the final lines are as evocative as they were when I first heard them. They provide a final dose of substance, hinting at the deeper turmoil of the writer’s experience. At the end, there is something memorable in something that would otherwise easily be forgotten.

A few weeks ago, in South Lake Tahoe in California and with heavy snow on the ground, I decided to trek up to a frozen lake. Given that this was a slightly longer than normal hike away from the main tourist areas, and mid-week, I expected the trail to be fairly quiet.

As it happened, I only saw one other person on the entire hike: a woman out with her two dogs, returning as I climbed the hill. We must have looked equally odd to each other: she was wearing denim and light trainers. I was in technical fabric, mountaineering boots, snowshoes, walking poles and carrying heavy camera gear.

What I like about America is that when you meet another walker on a trail, you’ll often stop for a chat: talk about the route, the area, the weather, your gear, whatever. The dog walker was no exception: she gave me a great tip-off about a point where I could go off trail to see a panorama view of a lake I knew to be just over a ridge to my right.

Other than this one encounter, my walk in the woods was an exercise in solitude. But more than human solitude, I started to realise there were no animal sounds either. Normally, you can expect to hear bird calls, the undergrowth rustling from the movement of an unseen creature. But none of that here. It was true isolation, and I quickly started to realise it. At one point, as I neared my final destination, I heard a crow cawing in a tree above.I practically jumped out of my skin.

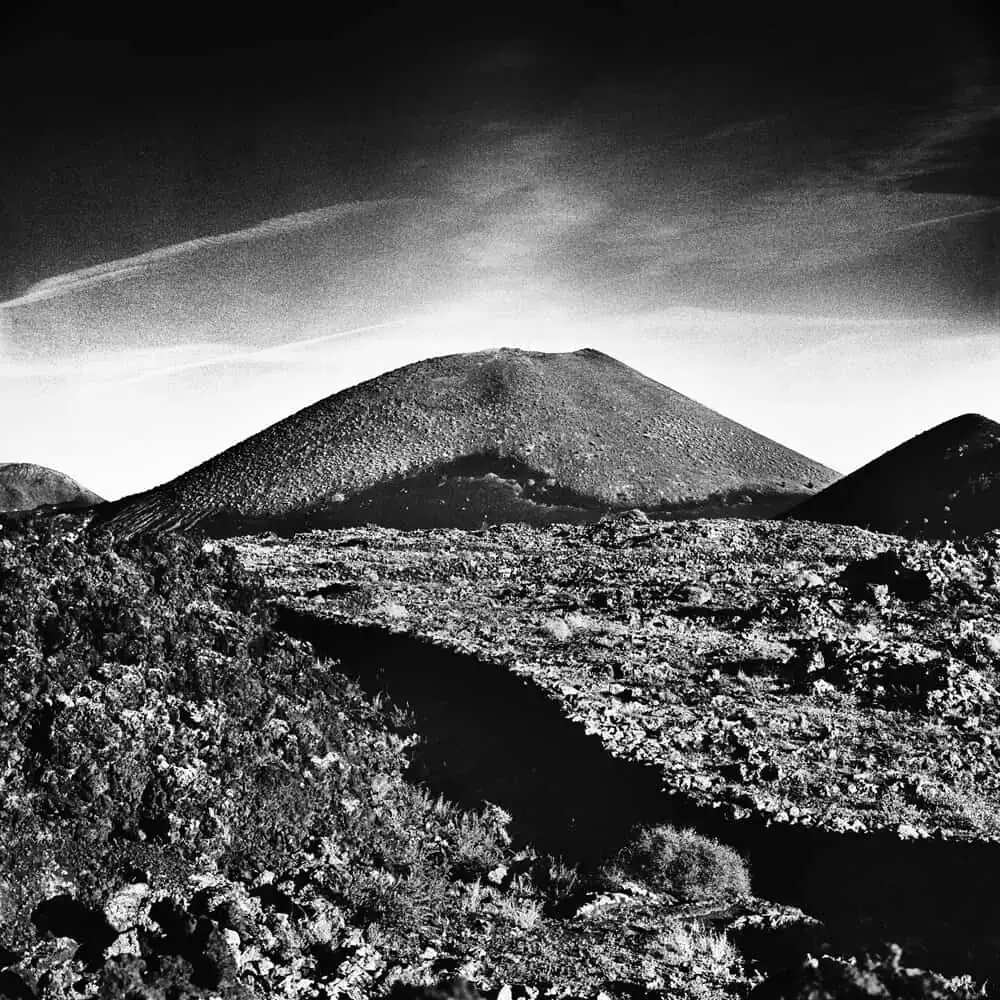

I’d encountered this once before. Well, I’d probably encountered it many times before, but only once that really stuck in my memory when I’d climbed Caldera Blanca – a volcano in Lanzarote. Caldera Blanca is a well-known and well-visited tourist destination, but that day, I’d arrived very early – as the Sun was rising – and at a quiet part of the season. The volcanic landscape is a desert and looking over the Timanfaya National park, you can not only hear minimal signs of life, but you can’t see any either: the lava flows extend to the coast without any visible buildings, roads or even paths. You can start to feel like the last person on Earth – indeed there’s something about that landscape that made me think of Charlton Heston in The Planet of The Apes. When I encountered a few goats as I picked my way around the crater’s rim, I was genuinely ecstatic to see them.

In hindsight, as I trekked up towards the frozen lake, I should have realised that my mind would start to play tricks on me. When I first saw the silhouetted backlit figure of the walker and her two dogs on the trail ahead of me, I thought it was a bear and her two cubs. Despite knowing it was still too early in the year for that, I had a moment of terror – just a second – before my senses took hold again.

My snowy trail continued up through a gorge following what I suppose from the occasional speed limit signs I passed, is a road in summer. With time, the trail emerged onto an open ridge and here I found a few huts that made up a wildfire lookout station – all locked up for the Winter. I saw some fantastic views out over the landscape, reached the frozen lake, was startled by the crow I mentioned earlier, saw more closed-up huts and turned back in time to see the sunset over the valley below.

Then it got dark.

This was no problem – In fact, I knew it would happen. I’m used to hiking in the dark – or at least finishing hiking in the dark. I carry a headlamp as a matter of course in my backpack and generally have a small power bank/torch combo in there as a backup too. But I don’t like to use them until it is absolutely necessary – as the light drops, your eyes adjust to the dark and you can see well and in far less light than you might think.

Many years ago, I worked in a commercial photographic darkroom, and much of my job was carried out in full blackout. I got used to carrying out delicate and precise tasks blind. Even in such total blackout, I often thought – or thought I thought – that I could make out shapes and forms in front of me: I knew my hand was there in front of me and I often felt I could make out its shape, black on darker black in the void. Then there were occasional lights in the void: pulling the tape off exposed roll film that joined it to its leader paper, or pulling sheet film from holders, I’d often see – or think I saw – a feint, milky blue-white glow. I thought this had something to do with static being discharged, but I never checked. I was dealing with light sensitive film, and I would have thought that the glow I saw – or thought I saw – would have shown up as light fogging on the film. But it never did. Maybe I was imagining it? I’ve often heard it said that when you remove one sense that your others heighten. But maybe it’s not just your senses. Maybe your imagination heightens too?

The instant you turn on your headlamp your eyes readjust and in an instant your world becomes a lot smaller. The stars above seem to dim – some even vanish. The differentiation between the ground and the trees and the trees and the sky disappears. To minimise this (and to preserve battery power on my lamp) I set it to its dimmest setting. This dim light is useless for illuminating distant objects, so I angle the torch downwards to light a patch just in front of me. I no longer concentrate on my wider environment – and I couldn’t even if I wanted to – but instead am limited to a dim circle of light a few meters wide in front of me. My concentration is now on my footsteps: are there tripping hazards ahead? Am I following the path? (When snowshoeing on a trail like this, and when there has been no fresh snow fall, it’s helpful to look for and follow the tracks your snowshoes left on the way out – in my case, they were distinctive and easy to spot and follow).

It’s a trick I’ve seen David Lynch use in several of his movies: a patch of road in motion, illuminated only by a car’s headlights and surrounded by the impenetrable dark. Filmed from the font of the vehicle. The driver’s point of view. You have a sense of motion and often of great speed. But only the motion. No landscape and no destination. No sense of safety or hazard or context. And this creates the hazard. You, the viewer, are journeying into the unknown.

To compliment this, the sound I experienced was purely from me: the crunch my snowshoes made as they hit the snow; the squeak of their hinges as I lifted my foot; the rustle and creak of the fabric I was wearing. All rhythmic sounds created and necessitated by my motion. I provided my own soundtrack.

When I first heard it, I ignored it – I just assumed it was a creak or a squeak from my backpack. Heavy lenses shifting inside causing the bag to pull on its frame. Then I heard it again and I stooped. But I still couldn’t be sure. Then, a third time and I knew it. A howl. A distant howl. I don’t know if it was a wolf, a coyote or just someone’s dog in a far-off back yard. I didn’t really matter. It broke my trance. For the last hour of my hike, I had disengaged from nature as my senses narrowed. I had become entrapped in a microcosm of my own creation. I had isolated myself from nature by being in nature.

The howl brought me back to reality. No, what I had been experiencing was already very real. The howl brought context back to my reality. I saw… or rather heard that I was no longer in my bubble.

Straight away, my rational brain felt wonder. Had I heard a wolf? If so, how marvellous! I didn’t feel threatened – after all, it sounded like it was a long way away. It was amazing. But then, as I realised the howling was continuing at regular intervals, something more primal kicked in. I knew the howl was distant. Likely very distant. But none the less, I looked over my shoulder. The head torch too dim, I turned it up to maximum brightness. Nothing. The last section of my hike – I don’t know how far – probably not long, though it did not seem so, was hiked at speed. I did not feel entirely comfortable until I was sat back in my car with the doors locked.

Driving back to our hotel afterwards, I pulled into a 7-Eleven to get something to drink.I asked the clerks – the first human contact I’d had in hours – about the howl.Had I heard the wolf?I didn’t get a definitive answer, but I did get a story about a bear.In hindsight, it was a ridiculous situation.Maybe I was just craving conversation after my experience – or a chance to just tell someone what had happened?

I’ve always thought of hiking as a meditative process.I let my mind wonder as I walk and often I’ll find myself thinking about things very different to what I’m experiencing.Deep winter brings with it its own set of challenges: for one thing you have to enclose yourself in so much gear that you can feel claustrophobic even in the great outdoors.The gear you wear also starts to cut into your senses: goggles limit your field of view – especially if they become fogged.Hats, hoods and helmets limit your hearing and thick layers and snowshoes limit your movement.Combine all this with how much smaller the pool of light from your torch makes the environment and you can start to feel like you are walking more through some abstracted space than an actual landscape.

I don’t think this is a bad thing – it’s just a thing that happens – but none the less it is interesting and even a bit surprising to experience.It’s useful to have something that you can reference to pull you out of your bubble: maybe it’s something you can plan for – like stopping for a while, turning off your light and waiting for your eyes to readjust- or maybe, like my howl, you stop because something makes you stop.Whatever I heard that night, I’m glad it pulled me out of my trance.